|

STEPHEN BISHOP

The following article was provided to me back in the

1970’s and was taken from an old book on Mammoth Cave supposedly

published in the 1870’s. Story presented in John Gorin Volume 1,

1763-1837 by Sandra K. Gorin,

Gorin Genealogical Publishing,

(c) 1998.

“The next map of Mammoth Cave was

made by a slave belonging to Franklin Gorin. Gorin lives in Glasgow

Junction, eighteen miles from the entrance of Mammoth Cave. [Note:

Franklin Gorin died in 1877 in Glasgow KY.] It is said he was the

first white child born in that region. He read law and practiced as

an attorney. Given the Kentucky penchant for suing, he became as

wealthy as any merchant, and looked about for an opportunity to

pyramid his money through investment.

“In the spring of 1838 Gorin

purchased the Mammoth Cave tract from the Gratz brothers for $5,000.

As tourist manager he retained Archibald Miller, Jr. The Mammoth

Cave Inn was enlarged to accommodate forty persons, and fences and

stables were built. One of the smartest things he did was to bring

in a new cave guide, his own slave from Glasgow, a black man named

Stephen Bishop. Stephen Bishop became one of the greatest cave

explorers in Mammoth Cave history. His work opened a new era, during

which the idea of connection emerged.

“Of the dozens of individuals who may

have been responsible for discovering one or more fragments of the

caves that would one day be connected in the Mammoth Cave Plateau,

the first about whom we know is Stephen Bishop. He was a slave sent

to Mammoth Cave to make money for his master, Franklin Gorin. Before

Stephen Bishop left Mammoth Cave, he had acquired an international

reputation as a cave explorer.

“Slavery in Kentucky reached a

high-water mark between 1820 and 1830. Its ebb was the result of

large landholders being split as fathers left farm to sons until

farming with slaves on a grand scale was impossible. Slaves were

expensive. A promising young black man might fetch $2000 at auction;

a black woman, $800. And from 1833, a law forbade the import of

slaves into Kentucky. Thus Franklin Gorin’s investment of a slave in

the enterprise at Mammoth Cave was somewhat unusual for the times.

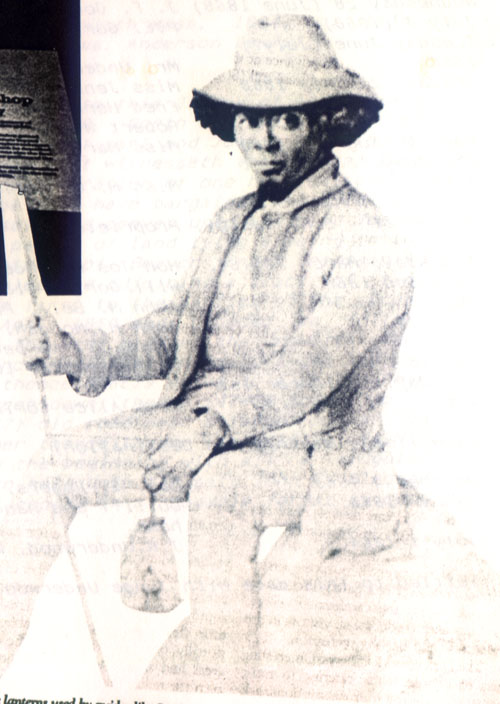

“Stephen Bishop was a young man of

enormous curiosity. He was about five feet four, lean and hard, with

the build of an athlete. In Mammoth Cave he moved effortlessly

across the tumbled rocks. He was quite intelligent, and was said

always to have an assured and tranquil air. He was a slave who had a

quiet pride that did not offend his master.

“In 1838, Stephen was put to work

learning the routes in Mammoth Cave from Archibald Miller, Jr., and

Joseph Shakelford, white guides who wee sons of former guides.

Stephen learned the spiel with no difficulty, and was soon

conducting visitors with ease over two or three miles of passages.

“The guide uniform of the day was

whatever Stephen and the others could get. Stephen wore a

chocolate-covered slouch hat, a jacket for warmth, and striped

trousers. Over his shoulder on a strap swung a canister of lamp oil.

In one hand he carried a basket of provision for the longer trips –

fried chicken, apples, biscuits, and often a bottle of white

lightning for refreshment. In the other hand he carried an oil

lantern – a tin dish holding oil and a wick, with a small heat

shield held above the flame by wires. Above the protector was a slit

through which he slipped his index finger.

index finger.

“Cave guiding was fine work. It was

fascinating to talk with the people who came great distances to see

Mammoth Cave. Stephen never conveyed any boredom with the old

trails, but he wondered about the holes leading off from the

commercial routes. He yearned to explore those beckoning passages.

“As the summer of 1838 wore on,

Stephen began to probe the obscure byways. In a part of Mammoth Cave

called the Main Cave, behind an enormous rock, the Giant’s Coffin,

he squeezed into a small room and down through a crack into a maze

of passages beneath. Here he found the fragments of a burned cane

torch and bits of grapevine tie left by ancient aborigines who had

explored Mammoth Cave before him. Stephen explored the maze until he

came to an awesome well-like hole over 100 feet down. Here he turned

back.

“Gorin was pleased with the news. All

hands went back to investigate. Gorin named the new pit Gorin’s

Dome, and sent a letter describing it to the newspapers. The account

brought adventures to Mammoth Cave. Most of them were content to go

on the guided tour, but others would pay to be taken deep into the

wild cave.

“Late in October 1838, the air was

crisp and cool. The color of the leaves ignited the forest with

blazes of yellow and red. One visitor to Mammoth Cave, H. C.

Stevenson, of Georgetown, Kentucky, spent several of those brilliant

days touring the cave. Stephen told him the story of the discovery

of Gorin’s Dome and of the difficult descent he had made with two

others to the bottom. Stevenson asked whether Stephen knew of other

passages where no men had gone before. Stevenson wanted to see some

real cave. Yes, Stephens aid, he knew where there was more virgin

cave. Did the visitor have guts? Yes, indeed.

“Stephen carried a lantern and a

basket of provisions. Stevenson brought another lantern. They

entered the cave, walked to the Giant’s Coffin, crawled behind it

into the low room, then they squeezed through the cave between the

wall and the floor, into a passage where they could walk easily.

They continued down the passage, pausing to toss rocks into the

depth of Sidesaddle Pit. The oil lamp was miserable for seeing any

distance, but they did not need to see the bottom. They could hear

how far down it was as rocks bashed against the walls and exploded

into little pieces.

“After returning to the main passage, they soon

reached the brink of Bottomless Pit, a gulf that started as a

vertical shaft on the left side of the passage. The pit extended

across the floor, cutting off further progress. Stevenson tossed a

rock into the void counting to himself. It took 2.5 seconds from the

moment of release, by his best estimate, before the rock splattered

to rest on the bottom. Stevenson held both oil lamps, lighting the

edge of the drop and the six-foot gap that blocked the way to the

continuation of the passage on the other side.

“The two explorers went into a side

passage to return with two cedar-pole ladders. Stephen cleaned off

the edge of the hold, scraping the rocks into Bottomless Pit. They

thrust the first of the ladders across the pit, jamming it on the

other side between two rocks. They rocked the ladder back and forth

until the pole ends were seated. This was the result of the talks

about what might be found if one could cross Bottomless Pit. The

more Stephen had talked, the more Stevenson had wanted to see for

himself.

“When all had been prepared, Stephen

sat down, straddling the ladder. He tested it with his weight,

rocking forward. It held. Now he was ready to go. He leaned forward

on his hands, scooted forward, moved his hands forward, and pushed

head again. He moved cautiously, a few inches at a time. Then he was

over the void. Stephen moved on across quickly. There was nothing

below to see except darkness. The pit was in shadow. It might have

been more frightening if he could have seen the bottom, but he was

interested in the other side. Now he rested his feet against the far

edge, quickly scooted forward, and went over on his hands and knees

on the other side of Bottomless Pit. Stephen let out his breath,

cleared some rock from the edge, and then told Stevenson to come

across. Stevenson bridged the second ladder over the drop. It was

longer and seemed safer. For an instant his light showed the depth

of the pit, and then he also was across.

“While Stevenson rested a moment,

Stephen checked around the corner. Here he found another chasm, this

one quite narrow. It could be jumped. Stevenson joined him to pause

at the brink, then each in turn stepped smoothly across. So far so

good. They had certainly moved far beyond the tourist realm. The

actual distance back to the tourist trail was not far, but the

formidable barriers they had crossed had taken them deep into an

unknown underground wilderness.

“Stephen was now eager to explore.

The last time he had gone off the beaten track he had found an

exciting new cave, much to the pleasure of his master and himself.

There had not been the risk that time. Now he had crossed a deep

pit, taking a paying customer with him. The element of risk and the

lure of the cave excited them both.

“The two explorers set off through an

oval passage in which an old stream had left banks of gravel. The

passage was tilted downward, taking them deeper into the earth. They

went on into a high, dry crouchway. The passage narrowed to only a

few feet wide, and the ceiling pushed them down into a stoop. The

smoke from the oil lamps was acrid, so they held the lamps at arm’s

length as the crack narrowed to a very tight squeeze. They forced

their way to the top of a narrow canyon, watching to keep their legs

from getting stuck. Beyond the narrow place the passage opened up

again into a fine, sand-floor walking passage.

“After several hundred feet they

entered a mud-floored room that was the junction of several

passages. It was an ideal situation for satisfying Stevenson’s

deepest desires. Stephen stood back as Stevenson walked across

first, putting a row of human footprints into the mud of the damp

floor. This is what he had come for, to be the first man to enter

those Stygian realms.

“Then they stood together on the

brink of a valley in a passage thirty feet wide and forty feet high.

They could see a stream of water below. Stephen stooped over and

made a mudball. He hurled it to splash in the deep expanse. They had

found the first real river known in the Mammoth Cave. They named it

River Styx. Stephen looked carefully, examining a possible route

downward along one wall to the water. But that would be for later.

Stevenson had had his day. It was time to leave the cave. Stephen

would come back later.

“The two retraced their steps to the

junction. Here the right hand led up a sandy slope. Stephen

scampered up, pausing to see that the passage at the top led onward

to the left and also branched to the right again. The passages were

wide open for exploration and were very tempting. Nevertheless, they

had the crossing back over Bottomless Pit to make. Until that

traverse became more familiar, explorers would feel very remote to

this part of Mammoth Cave. One last look, and they then crossed

their rough bridge again.

“Back at the inn, they told of their

adventures. Stephen stood back while Stevenson talked. Gorin was

ecstatic, partly over the contagious excitement of Stephen and

Stevenson, and party because Stephen had – in a few months –

discovered more new cave passages in Mammoth Cave than all the other

guides together. From the merry, confident look in Stephen’s eyes,

Gorin knew there was more to come.

“Stephen had established himself as a

great cave explorer. But if he were promoted as the first great

caver in America, he himself knew better. He had found evidence that

prehistoric people had explored far back into Mammoth Cave. And he

knew that more than eight miles of Mammoth Cave had been explored

before he was born, by men whose names he probably knew, but which

are now lost to us. Most of the former discoveries, however, were

made in easy walking passages. The dimension Stephen added was that

of the publicity given to them were the starting point of a kind of

tenacious modern exploration. He pushed, relentlessly through every

passage that was in any way passable, in hopes of finding big

discoveries beyond.

“During the slack tourist days that

followed the crossing, a bridge of cedar poles was constructed

across Bottomless Pit. Now many long trips were made into the near

area of Mammoth Cave, to discover, explore, and name Pensacola

Avenue, Bunyan’s Way, Winding Way, the Great Relief Hall, and deep

into the depths, the mud-encased River Styx. Mammoth Cave had

exploded. Stephen explored continuously through the winter.

‘Where others feared, Stephen

cautiously kicked his heels into the mud slope leading down to River

Styx. He could see the bottom through the water after his eyes grew

accustomed to the reflections of the ceiling. One remarkable

discovery was that the new river contained blind white fish a few

inches long. Stephen caught some for exhibit. He waded across the

river, climbed the mud bank on the other side, and found an opening

leading to a crouchway. It would be another place to explore when

the bigger river passes had all been looked at.

“Gorin was most pleased. In one

winter, Stephen had doubled the known length of the Mammoth Cave. If

newspapers editors had gone wild over accounts of the discovery of

Gorin’s Dome, what would they make of these sensational new

discoveries?

“Gorin wasted no time. From Thomas

Bransford of Nashville, he hired two slaves for $100 a year each.

These slaves, Matterson Bransford and Nicholas Bransford, were

trained by Stephen to guide on the tourist trails of Mammoth Cave.

Stephen was a good teacher, and the new guides wee soon operating

completely.

“Tourists began to arrive in the

spring of 1839. Gorin’s inn was overwhelmed and the guide force was

kept busy with the steady stream of visitors. They came on horseback

and by wagon from Bell’s Tavern on the main highway. These were good

times in Kentucky. Gorin saw the business increasing, and concluded

that he had better invest more capital in Mammoth Cave, or perhaps

sell it to a favored buyer.”

Followup: Franklin Gorin did sell the cave to Dr.

John Croghan, a distant relative, from Louisville. He offered

Stephen his freedom many times, but Stephen liked it the way it was.

He chose to stay at the cave and work with Dr. Croghan who was to

set up an experimental tuberculosis hospital in the cave, trusting

that the constant temperatures and humidity would be a cure. It was

doomed to failure with nearly everyone dying. Stephen was set free

in 1856 but he never made it to Liberia where he had been saving to

go with his wife and family, he died in 1857 and is buried at the

cave. His widow remained near the cave and later married another

cave guide by the name of William Garvin. Stephen’s name is carved

or smoked throughout the cave, normally right next to Franklin’s

name. One graffiti found fairly recently showed his signature as

Stephen Gorin. Before his death, Stephen drew a map of Mammoth Cave

that was extremely accurate; copies are still available. He was

often called ‘The Columbus of Mammoth Cave.” Stephen claimed a

French/black heritage, from pictures it appears that he was likely

mulatto. His parentage is unknown.

See Also:

Emancipation Orders for the slaves of Jno Croghan

Franklin Gorin wrote of Stephen before his death: “I

placed a guide in the cave – the celebrated Stephen, and he aided in

making the discoveries. He was the first person who ever crossed the

Bottomless Pit, and he, myself, and another person whose name I have

forgotten, were the only persons ever at the bottom of Gorin’s Dome

to my knowledge. “ In other statements, Franklin stated that Stephen

was extremely well educated, spoke several languages, understood

Latin and was the lady’s choice as guide when they came to the cave.

In 1991, Mammoth Cave celebrated its 50th

anniversary as a national park. My daughters and I visited Mammoth

Cave National Park and stopped to listen to a program put on by the

older tour guides. After their presentation, I spoke to the park

historian, introduced my daughters as closely related to Franklin

Gorin and told him that back in 1960 I had taken a long tour of the

cave and remembered a place called Gorin’s Dome – this being many

years before I had married a Gorin. This gentleman introduced us to

several others as they recognized the name and a quiet discussion

was held, including the author of “The Longest Cave” and other fine

books on Mammoth Cave, Richard Brucker. We were approached and asked

if we could stay around until the next tour and explained that

Gorin’s Dome and the Bottomless Pit had not been on a regular tour

for many years. We said yes, and were told to get in line for the

next Historical Tour at no charge. We were told to go back to the

end of the line. The tour started and we walked down with about 40

others, the old steps to the entrance of the cave. The tour started

when the “trailer” came up to us and asked if we were the Gorin

family. A trailer is the guide who follows a large group into the

cave to be sure nothing happens to anyone. When we identified

ourselves, he motioned for us to follow him. We went over to the

Giant’s Coffin mentioned in the article above, not too deep into the

tour. We walked through a narrow passage behind the coffin where

sitting on the floor of the cave were three hard hats with lanterns,

knee pads and other equipment. And yes, he was taking us to Gorin’s

Dome. We walked, crawled, shinnied and squeezed for what seemed like

a long time before our guide came to a halt. He then picked up about

a dozen torches which he threw up into the air as high as he could

and there, illuminated in the fire of the torch, was Gorin’s Dome.

He repeated this several times so I could take some photographs. We

turned around and there was the Bottomless Pit. It was such an

awesome experience – one could, in the darkness, sense the very

presence of Stephen as he gazed upon this wondrous site, first

discovered by dear Stephen Bishop. We shall never forget the

experience.

|