What Ever Happened to Avondale?

Long Run Branch in the

Avondale District, 1861 - 1965

Ashland, Kentucky

If you are looking for old

Avondale, the notorious district of Ashland, step inside the wire gate to the

Tennis Center at the corner of Oakview Road and 13th Street. Beside the clear

waters of Long Run Branch, on the grassy bank is a limestone boulder inscribed:

In memory of their son

Stuart Monroe Blazer

Born in Ashland on October 9, 1927

Killed in Action in Korea on October 14, 1952.

This Tennis Center is a gift to the people of Ashland

From the foundation established by Georgia and Paul Garrett Blazer

This isn't old Avondale either, but on this spot, Nora Christiana Weidenheller met Mrs. McGuire under her sycamore tree; where Nora Christina gathered the children of Avondale to begin her mission. While the monument to Stuart Monroe Blazer marks the end of his heroic life, it symbolizes a new beginning for Avondale children back in 1939.

Step back, look across the parking lot for Tabet's store. It was perched onto the corner of Oakview and 13th Streets. Nearly everyone had a charge account there until payday. The rest of Avondale -- homes and shacks, abandoned cars -- was spread across the Branch. For many, Avondale still lives through memories, stories, maps and records.

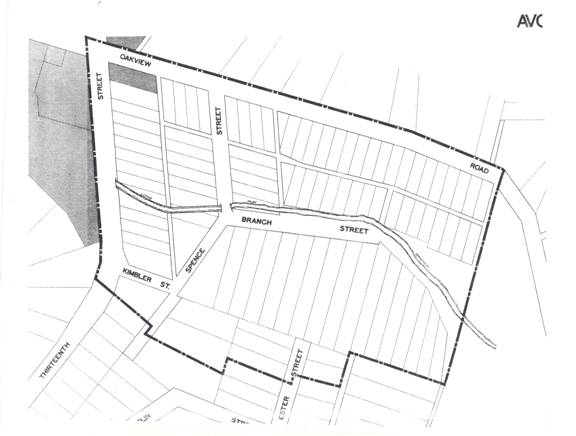

Avondale was a half moon shaped parcel of left-over land. It sprawled along both sides of Long Run Branch to front the 1200 block of 13th Street. It sidled back on Oakview Road where many black families settled and built their homes.

Real families lived in Avondale with plans and dreams, and, yes, there were shacks of decrepitude and some ruined lives, until Urban Renewal condemned Avondale in 1963. Yes, condemned, because City experts believed it could not be redeemed any other way.

I grew up in Carter County, far out in

the country on a tobacco farm, and I knew nothing of Avondale until my quest to

tell the story of my cousins, the Fannin children. They lived in Avondale off

and on during the 1960s, and, in between these times, they went to the Ramey

Children's Home in Ashland. Many of the children in the Ramey Home also had

roots in Avondale, before Gertrude Ramey took them in. While they were not my

cousins, they wanted to tell their stories, too. Like Ms. Weidenheller, who you

will meet, she asked the same question, “How did a myriad of children come

together in the Avondale district?”

As for me, I wonder what ever

happened to those children; do we believe poverty, disease and death are still

the greatest character builders? And, finally where did Avondale go?

"We burned one or two shacks at a time for practice. It was roach and rat-infested place full of dilapidated shacks. After we burned nearly everything, the bulldozers and front-end loaders scooped up the rubbish, Avondale was reborn." stated James C. Hogsten, Assistant Fire Chief.

Who doesn't remember 13th Street hill? If you drove slowly, you caught sight of men playing dice on the rickety bridge across the branch; children catching lightening bugs at dusk; a fight over gambling or almost anything; and Policeman Earl Borders, shooting as he ran, chasing Virgil Spradlin. "It was better than the western movies on Saturday night," Frances Johnson quipped. "Those policemen acted like cowboys. We sat on the front porch and watched it all, every Saturday night and sometimes on other nights too."

"When the police came it wasn't always sinister," Virgie Kelley said.

"Sometimes boys had stolen food from Evans Market; they ran through the culvert and hid there from Earl Borders. They'd throw things at him and taunt him, and he tried to scare them."

For its small size -- twelve acres

more or less -- Avondale had a grand name, and a large history to match with

several owners and land speculators taking an interest in it. D. A.

Leffingwell was not the first owner of record, but it was he who named it

Avondale and imprinted the street names: Spence and Branch. Before that,

several investors wanted to fix it up, subdivide it and make a little money. James and Harriet Haskel purchased the parcel

from Nichols and Bayless in 1861 and renamed it Long Run Development. Haskell

proposed street names for trees: Lombardy, Poplar and Chestnut, perhaps in

favor of Oakview Road. As a patriot, he

tagged on Columbia and Broadway. He sold out to Leffingwell in 1896. While

Leffingwell may have given considerable thought to the Avondale name, perhaps

he named it for Avon, New York, where he was born. And, who knows if he did, but did

he envision tennis courts?

Avondale had lots of promise as its colorful life attests. In the early nineteenth century, it was a haven for families to enjoy just as it is today with shady corners and round stones to throw into the clear water. But, in between 1896, after Mr. Leffingwell filed his deed, and 1965, when the bulldozers scraped off the polluted topsoil of Avondale, it became notorious like its most flamboyant owner, George S. Kimbler.

As early as December of 1905, Mr. Kimbler collected little pieces of Avondale; he purchased Lots 39, 40, and 41 on the corner of Branch and Spence streets. The ground was wet and low and the price was cheap. There, using bark slabs and second-class lumber, he built the first shacks on the wet ground, with no foundations. He rented them out to poor people for cash on the spot.

Born on a hardscrabble farm at East Fork of the Little Sandy; he was a poor man himself, but he was a clever man, and he soon became an unscrupulous landlord. He promised to replace broken windows and haul away the refuse, but he never did. He purchased more squares as he could until he owned nearly all of Avondale, and by 1944, he did own both sides of Branch Street. It was Kimbler who designed the heart of the Avondale slum on Branch Street, fueled by his greed, broken promises, and neglect.

Long Run Branch made its contribution, too. Flood after flood honed the branch into a deep channel. On its waterway to the Ohio River, it crossed the Midland Trail through a culvert at the base of the hill. Wagon teams headed to Cannonsburg, watered livestock or topped off a hot radiator. But in the 20th century, children lived in Kimbler's shacks; the water posed a real danger. With each rain, the water rose over the plank floors in the shacks. For that reason, many of them had dirt floors. Out came the big rats, followed by the health department with typhoid shots for the children.

Avondale was always valued for its natural beauty, but early on Haskell and Leffingwell wanted profits too. A long time before it was annexed to Ashland City, with the savagery of a surveyor's sextant, more than one developer squeezed the parcel into tiny home sites, at least on paper.

D. A. Leffingwell was Superintendent of the Clinton Fire Brick works. He traded in real estate, too. In a hand-drawn schematic, he designed a cross with Branch Street as the stanchion. Spence Street, the only other street, was the cross bar. It was named for the Spence family, who purchased one of the first squares. Engineers, Boggess and Gesling, fine-tuned the plan. Leffingwell referred to the Haskell Addition location as, 'Near Ashland,' until he re-named it, Avondale.

Leffingwell's design was indelible, or so it seemed. His map withstood several revisions and perhaps some embarrassment for City fathers because it attracted squatters, and everything and everybody in Avondale was visible to traffic.

He set out seventy home sites on twelve acres. In August of 1900, James H. Poage got involved. He designed fourteen front sites, fifty by two hundred twenty-five feet deep along the County Road subsequently called Cannonsburg Road as it abutted the east end of the Midland Trail. It was clear: they expected commercial development along the Cannonsburg-Midland Trail, but Poage was greedy, too; his lots were too narrow. Especially those fronting the main road where a few commercial buildings sprang up in tandem with Kimbler's rough lumber huts. It all fell into decay though, just like the shacks on Branch Street; a slum in the 20th century. Lack of cash money, coupled with this unpredictable run-off feature of Long Run Branch may have stymied actual development, because, so far, the different versions of lot design were confined to the engineer's schematic.

Still, proverbial dampness and flooding problems extended Avondale's promise of profits well into the late 20th century until, at last, City fathers, under pressure from George Kimbler, built a half-hearted bridge across roguish Long Run Branch in front of Kimbler's shanty town shacks and the Avondale Chapel. It was wide enough for two cars to pass although none ever did try.

WPA workers did their finest work to shore the banks with chiseled square boulders, but nothing they did mastered the restless water. Long Run Branch always won. Sudden flashfloods turned Branch Street into a sewer lake with rats and snakes swimming for high ground.

Nora Christina Hatch Weidenheller drove by Avondale on a regular basis. She was a produce dealer in her family store on Greenup Avenue. Disdainful of the developing downtrodden district with ragged children and idle men, she prayed about it. Then in her pragmatic way, she interpreted this problem as one God wanted her to solve. She persuaded the Rev. W. K. Woods of Pollard Baptist Church to establish a mission, and to name her its superintendent. In a bold move, despite its reputation for discord, she went to Avondale to invite people to come to Pollard Baptist Church.

Mrs. MacGuire rocked in her chair under a giant sycamore when Nora Christina walked up. "Why not bring church to Avondale?" Mrs. McGuire posited. "The children need everything, including spiritual awakening." Twice a week, Nora Christina brought Bible stories, treats and games to the eager children as they got acquainted under the sycamore tree. The gamblers and drunks, who dominated Branch Street, took their games out of sight.

Working through the muck and

unpleasant surroundings, Nora Chrisina reported, "There was no pavement in

Avondale. In the summer time, the dust strangled you and in the wintertime the

mud and water was well over our overshoes. Before we had a building, Wilson G.

Salmon let us meet in his garage on Oakview Road. There we laid rough lumber on

concrete blocks for seats. We poured sawdust on the dirt floor. Dorothy Adams

volunteered to help us. Mrs. Crayton Grimet led the singing. That same year, on

a special day in 1939, we broke ground for our new Avondale chapel. Our mission thrived; until 1963 when the

Federal Government condemned Avondale for urban renewal."

Right in the hotbed of trouble, near the bridge, Nora Christina's congregation built Avondale Chapel Mission at 1439 Branch Street. It was a humble beginning, but a magnificent demonstration of Christian kindness. Nearly every day, the children watched drunken brawls and abuse. They were deprived of positive attention and stimulation. Nora Christina and her workers took the edge off the way poverty whittles at the spirit. They brought love and order to the children’s lives. Soon, Poe Jeffrey Williams, superintendent of Church Sunday services, expanded the Avondale programs. Vacation Bible school attracted the Johnson children and many others. Now, Avondale had two places of worship, but the Baptist chapel had one purpose, to save the children.

Perhaps Nora Christina inspired their parents too. Laborers, down on their luck, took any job that was offered. Robert Johnson, Ashland City Clerk (1965-1966) recalls refuse pickup service in the early 1960s depended upon Avondale workers, Hanners, James, Clifton, Rowe, and others to manage the trucks.

"They collected garbage for the city, worked on the railroad, and performed odd jobs," Johnson explained. Blanch Johnson; mother to eleven children cleaned other people’s houses to support her family. She walked all over Ashland to work.

Avondale already had a church. Four years earlier in 1935, Kimbler built his own Church of God Holiness higher up on Spence Street and declared himself, Evangelist. He handed out cards with his picture holding a bible in one hand and with the other, jabbing his finger at the sinner.

Of record, he had more than one wife and with them, he fathered eleven children. As he built more shacks for poor people, on the flood plain, he moved his family farther up ground to a large white house on the side of the 13th Street hill that was once used as a hospital.

People in Avondale had more than their share of violence. After Nellie Fitch's own brother, Ulysses Sparks, shot her husband, Fred Fitch, Nellie walked to work, too. She had six children to feed. Each morning before dawn, she left her home in Avondale to wait tables at the B&L Restaurant on Greenup Avenue for 50 cents an hour.

Not everybody was changed; there were some loafers and shysters; they wanted good fortune too. They played cards and tossed dice on the footbridge and gambled what they had on their futures. Counted among the clever ones though was Mr. Kimbler, the major landlord in Avondale. He impounded their few cash dollar winnings for rent.

Once there, it was a struggle to find a way out; sometimes poverty tries to defeat people, and people refuse to let it. Virgie Kelly was born in Avondale at 1422 Branch Street in 1943; she was the elder of her mother's eight children. Her father, Reed Kelley worked for the city of Ashland.

"Each morning I made breakfast and tended to my brothers and sisters, but we never had enough food to eat. Mother kept me out of school each time she had a baby, so I fell behind.

I was scrubbing clothes with my hands when I was eight. When I was fourteen, I heard the Cunningham family needed help. Each morning I walked a mile to their home on 13th and Lexington to straightened beds, make their breakfast, and to clean up; then I walked back to Avondale to make lunch for mother. She was very sick one time because she had twins and only one survived. That done, I made my second trip to the Cunninghams to cook their supper, clean up and return to Avondale to make supper for us," she recalled.

. "I am blind in my right eye from birth. Miss Preston, the principal at Putnam School made a plan to send me to Berea for special training; mostly she wanted to save me. My parents refused. Formal school was over for me at fifteen." She recalls. "Our parents were strict. We were not allowed to leave our yard or to go anywhere, even to church. Perhaps it was to protect us, but I think it was to keep me working. The only exception was Christmas, when the Moore Tabernacle bus picked us Kelley children up for their Christmas Party. They gave us sacks of treats," Virgie said.

"After that, all day every day, I puzzled on how to get out of Avondale, and how to get away from home. So, I married an old man from Carter County who also mistreated me; but I did escape from home, and from him. I moved to Kansas for twenty-eight years. I studied for my CMA and then achieved my CNA in 1992," Virgie spoke with pride.

"I remember Ma Kelly and Mr. Tackett. She was a midwife who helped my mother with her babies. She kept a cozy house and rocked in her chair in front of her coal fireplace telling stories. When she finished a story, she pursed her lips and said, "That's what." Ever so often, she stopped rocking to spit tobacco juice at the hot coal chunks to hear it sizzle and to watch it splatter. She lived with Mr. Tackett.

Ma Kelly was rotund and not very tall; she looked a lot like Aunt Bee with her hair pulled straight back into a knot. Sometimes Ma Kelly gave us an apple or something else to eat."

Mr. Tackett was a dreamer of small dreams; "He fixed up an old wheelbarrow with side rails, and pushed it across 13th street to salvage vegetables in bins behind Evans market. He sorted it out and re-sold the good stuff to us for pennies," Virgie said.

Walter and Blanch Johnson, one of several black families to buy land in Avondale, reared children in a home they built themselves. Walter shined shoes and worked for Steen Funeral Service. Blanch worked in domestic service.

"Besides my mother, Blanch Johnson, Mrs. Weidenheller influenced my life the most of anyone. Mrs. Weidenheller came to our house, knocked on our door, got my mother to come to church. That changed our lives. She even bought shoes for us children so we had shoes for school. She really loved us, and we loved her," remarked, Jerry Johnson, one of the children.

It was 1942, when Walter, Sr. and Blanch Johnson bought their square at 1211 Spence Street, next to the alley, and built their house a little bit at a time. Walter was a complex man with many skills. He sang baritone, organized a touring band, was a WWI veteran but he was a black man trying to make a living in the 1950s. He found work at Steen Funeral home. He was also an educated man who kept records and wrote his family history in detail. His sister, Thelma Johnson, a graduate of Eastern Kentucky University, taught music.

Walter Johnson, Jr., graduated from the School for the Deaf in Danville and worked as a sign painter. He developed logos for Ashland businesses. His work is still evident on Greenup Avenue. He was also a skilled magician.

Jerry Johnson is also a well-known

artist whose early life in Avondale was shaped by his parent's work ethic.

Their sister, Eleanor, achieved success as a nurse. Eleanor related, "As soon as I understood my

mother was scrubbing floors on her knees, I asked to go with her. I was

thirteen. Right away, I learned to help. Mother worked for Dorothy Steel, a

schoolteacher, who taught me how to keep a proper home. This attention from

Mrs. Steel boosted my confidence to help my mother. Later I studied nursing at the Ashland

vocational school.”

“Of course, this was the 1950s, and there was job discrimination. Our father hardly found work; my mother ate lunch on the back porch at Miss Steele's house. Once when we first came to Ashland, we lived at a hotel on 29th Street, but we couldn't pay the bill. They set us children out on the sidewalk. Our dad took us to work with him and Mrs. Steen gave us food.” Eleanor concluded.

Sidney, the elder Johnson sister won a scholarship to Paine College in Augusta, Georgia to study opera. Charles, James and Jerry joined the armed forces. Frances and Connie worked in hair styling.

"There was no racial

discrimination within Avondale itself.

We children played together, shared our toys and loved each other. I was

enrolled at Booker T. Washington School when integration was ordered. I walked to Booker T., in the mornings but at

noon, I was required to walk to Ashland High School for afternoon classes. That

was Ashland's interpretation of integration,” Frances Johnson revealed,

It wasn't easy to live in Avondale, even when residents helped one another, and there is plenty of evidence of that. In outward appearance, it was a community of small bleak homes in need of windows, in need of modern sewers and a dependable supply of fresh water. As it stood, each resident was responsible for paying the city of Ashland for fresh water and power. That was not always possible, so they borrowed fresh water or dipped it out of the branch.

In a way, Avondale folks lived in a tawdry stage play, set on 13th Street at Oakview Road; their lives were on display. Their district was the most talked about section of an otherwise sparkling City. Traffic crept up 13th Street hill as drivers peered over their shoulders to catch a glimpse of windowless gray buildings, while ragged children made mud pies too close to the Branch, and one baby did drown. Drivers saw idle men playing cards in the bushes during the workday. At night, they built little fires to gamble through the night. Some gawkers came to find cheap labor, or spot a friend for the night. Avondale still had a lot of promise but the Leffingwell vision had changed.

By some accounts, Avondale fulfilled dreams too, but its legend always moved in tandem and sway with the demands of land speculators, even as it was transformed from a slum into a tennis center.

"My father, Frank Tabet and my brother, Joe Tabet bought the Caudill's grocery store in 1954 and changed the name to Tabet's. But, my brother moved away, and didn't want to work at it anymore. My sister, Leonie, and I took over. I was back from college and eager to work. The store was in the lower floor of a white stone building with four apartments upstairs. We rented them out. We closed up and sold it to Ashland Oil on August 20, 1959. The City bought it for the tennis courts," Nada Tabet reported in 2007.

The magic of the Blazer gift and Urban Renewal changed the image of Ashland on its west entrance. This was a relief to nearly everyone, except for Nora Christina Weidenheller. She saw this takeover as a cure for nothing. She was dismayed to see her people forced out. The children she loved and their parents scattered to all parts of the county.

The Avondale Baptist Mission was the centerpiece of her life. She worked to the very end of Avondale until at last she, too, watched the Chapel and the homes burn one by one.

She was not the only holdout. Before 1965, when Walter Johnson refused to sell out to Mr. Kell, even before Ulysses Sparks shot Fred Fitch on the bridge in 1962, way back before George Kimbler died in 1949 and didn't clean up Avondale as he'd promised the Judge, after sixty-nine years --the knell sounded for Avondale. Perhaps it was the Saturday night shootouts on Branch Street, or the flooding, the disease and abandoned children, but when the front-end loaders drove onto the corner of Oakview Road and 13th Street, they left no trace of brick, board or spirit. The Ashland Fire Department had already burned the shacks for practice sessions.

Early in July 1965, City Manager James Kell briefed the Ashland Chamber of Commerce on the first acquisition of Avondale land. He reported plans for transfer of thirteen acres from private ownership to the city of Ashland, including the Blazer's gift donated in honor of their son, Stuart Monroe Blazer.

Transition of Avondale district, was not a pretty sight to witness, but nobody cautioned Mr. Kell. In August 1965, he installed large signs on 13th Street and Oakview Road to point out to passers-by who may have already chosen to ignore the news reports, that the Avondale Redevelopment Project was wedded with the Urban renewal agency and with the city of Ashland under Title I of the Federal Housing Act of 1949, and it was working. And so, it was, with fourteen land titles in hand at a cost of $125,000 and forty more to acquire. But, there were holdouts. The widow, Edith Kimbler, was not anxious to sell, nor were Walter and Blanch Johnson.

City intervention wasn't new to Avondale, but other attempts to reinvent it had been futile. Was obliteration the only way?

The most deadly shootings, stabbings and brawls occurred along Branch Street in this concentration of hot energy, drink and gambling, and right in front of the Baptist Chapel.

When police cars roared into Avondale, it was in convoy with sirens and lights flashing, with four policemen in each car. Not even policemen, Earl Borders or Red Stapleton, had the courage to come to Avondale, alone.

"They left their motors running for a fast get out," mused Charlie Rouse, one of the children.

As late as 1962, men in Avondale went on settling their differences in public. So it happened on Saturday afternoon, October 10, Fred Fitch and his brother in law, Ulysses Sparks drove off to see a woman. That they were married men with several children did not deter them. Far into the country, they argued, and Fred was forced to hitchhike back to Avondale. Ulysses was waiting; he shot Fred in the stomach with a .22 rifle and beat the gun to pieces over his head while Fred bled to death.

These drunken self-indulgent men wanted to kill each other. Their children stared. Fitch died and Ulysses went to prison. This killing may have been the final violent death in Avondale. It brought out another convoy of police with Capt. James Richardson, Patrolmen Earl Borders and William Johnson investigating, and it made City authorities wearier of these episodes.

The death knell had already sounded though, when Ashland Oil bought the Tabet corner in August, 1959.There was no reprieve for Avondale.

Kimbler boasted he owned property all around Boyd County. "My houses are good enough for common people," he declared at his trial when he was charged for maintaining a slum not fit for human habitation.

"Our Fire Chief for fifty years, Burris Hensley, told us Mr. Kimbler kept a five-gallon can handy; he claimed it held water in case of fire. When Kimbler wanted to destroy one of his shacks for the insurance, and a shack caught afire, or maybe he set the fire himself, Kimbler ran out with his can and poured 'water' on the blaze - to burn it fast." James C. Hogsten, Chief, Ashland Fire Department.

John Mullins lived in Avondale in 1942. He worked as a waiter. He also set up a little grocery store at 1238 13th Street. His business did not last long. Soon after Mullins closed his store, Kimbler rented the empty storeroom to Albert and Magdalena Waugh and their six children. The large glass windows still plastered with advertising signs were open to passing traffic in plain view on 13th Street. Albert Waugh abandoned his wife Magdalena and their children to survive as they might, alone and with sewage seeping up through the ground. They drank branch water and scrounged for food, until April of 1944.

While some residents moved into Avondale until they found other housing, the Spence family bought land. Mr. Spence was an Ashland City policeman. His family was another of several black families on Oakview Road. Spence Street was the only access from Oakview Road. From there, it traversed west across the end of Branch Street, and upward into Heflin Heights, an annex to Avondale, platted in 1923.

In that same year, according to the plat map, a ten feet wide alley was named Canton Place. It was roughed out behind the first row of Midland Trail frontage lots. On one side of Branch Street, the lots measured thirty feet wide by eighty-seven feet deep and followed the meander of Long Run Branch. Ten lots platted on the west side promised larger lots forty feet wide and extended to two hundred eighty feet deep. But, this re-design was still confined to the paper schematic and Mr. Kimbler had bought up these lots too.

In 1925, Avondale was redefined, again. Poised for a buy out, Ashland City Engineer Charles D. Boggess set the number of front lots along the Cannonsburg - Midland Trail at thirteen. He scraped up every inch of ground as his predecessors had done and set widths at thirty feet, and also reduced the number of lots along Oakview Road. Still, his ideas were confined to paper because the Leffingwell imprint of 1897 was indelible. Avondale's name stuck and the two main streets he laid out, Spence and Branch Streets, remained.

On the corner of Oakview and the Midland Trail, Jeff and Bessie Caudill advertised general merchandise for sale from 1924 through 1938. Caudill's transitioned to subsequent owners Elbert Gilliam and to Joseph Tabet in 1954.

"My sister, Leonie Tabet, and I took over Tabet's store. There were always children playing around, and they were hungry. We cooked for them, made bologna sandwiches and even bought shoes for them. Their parents didn't work or drank up their money, if they did work.

It wasn't easy. Sometimes our customers took bankruptcy and put their debt to us on the list. But later they came back and paid us. I guess they respected us. We were good to them."

In the lower back part of Avondale, at 1418 Branch Street, across the street from the Baptist Chapel, another of Kimbler's most dilapidated shacks lured Felty Fannin. With eight children, he was on the run again from truancy officers in Carter County. That first night, September 16, 1962, Imogene Fannin gave birth to Andrew Jackson Fannin with the help of Ma Kelly, the Avondale midwife. The next day, Kings Daughters Emergency Room Doctors placed Andrew in an incubator and alerted Social Worker America Holbrook. Andrew Jackson was blind. Blinded from lack of sanitation at Avondale? Or made blind at the hospital by excess oxygen in his incubator?

"I remember Mrs. Fannin had a baby here and took it to the hospital and they kept it, wouldn't give it back to her." Anna Belle Everett said.

Wherever the responsibility lay, for baby Andrew, it meant tragic permanent blindness and a life of foster care with five families.

"I saw Felty and Imogene in passing. He drove an old car. He lived further up Branch Street, in an awful house. He made it more awful when he ripped up the wood boards in his floor to burn for heat, because he didn't have firewood. For that reason, his house and some others in Avondale had dirt floors."

Social Worker, America Holbrook, removed the Fannin children to the Ramey Home more than once during the 1960s.

By that time, the gouged out banks of Long Run Branch were eroded and littered with debris and that was the only place for children to play. The district held out hope for a sparkling future but harbored instead a miserable collection of Kimbler shacks, memories and records of discord, vice and poverty. Its main export over its history was the plethora of neglected children. Christina Weidenheller worked to change that, as did Gertrude Ramey. After she took in Jeffrey Ellison, Gertrude went to his mother with food vouchers for Tabet's store to see that the other children still at home were fed.

Upon occasion, a desperate Avondale mother rescued her own children from Kimbler's shacks. In 1944, Anna Belle Sullivan-Terry summarily deposited five of her children with Gertrude Ramey. Like a lending library, at different times, she came for one of her children, only to return with her new baby.

Ella Moore Rowe had little choice. She dissolved her family of young children for their own protection. She filed charges against her drunken husband, Freddie Rowe, for child abandonment in April 1944. Freddie fought back. He summoned Clay Caskey, also from Avondale, and his brother, Ed Rowe, for character witnesses; Freddie gave in though and confessed his responsibility and hopelessness as a drunk. He was indicted by the Grand Jury and sentenced to prison for five years.

Judge E. K. Rose offered Rowe provisional relief. But, despite the threat of certain prison, and with a job at Ashland Oil, earning $11.40 a day, Freddie floundered. He could not stop drinking. He was arrested for breach of peace and other offenses in Ashland City and still would not support his family. In January 1946, Ella signed her final complaint of record against Freddie, but the court was either unable or unwilling to persuade Freddie Rowe to support his children.

At last, Ella surrendered their children who remained in her care: Oma, Bud, Lillian, Helen, Mabel, Frank Ed, and Cora Lee to the Ramey Home. Gertrude kept as many as she could. Judge Rose sent two older girls, Oma and Lillian, to reform schools.

In early spring of 1944, the Health Department found courage to file neglect charges against George S. Kimbler when a seven-month old boy was discovered abandoned in his Mullins store building at 1238 13th Street near Long Run Branch, where it crossed the Midland Trail.

When welfare authorities rescued infant Ronnie Waugh, he lay on a soiled mattress covered by black flies. His sisters, Darlene, Marjorie, Virginia, Phyllis and brother, Ralph -- all under the age of ten -- hovered around their little brother. They had no food. These children did not belong to Kimbler, but the old storefront did. He knew they were there.

Their mother, Magdalena Skaggs Waugh, was not charged for her crime of abandonment, but Health Department authorities returned to investigate living conditions of Avondale District. They found children playing on sewage, a lack of fresh water, broken windows, and no screens to keep out flies. The Department of Health had already treated sickly children and several cases of venereal disease for single women living in Avondale. They also came out after each flood to give typhoid shots. They had the health records, after all. The Waugh children went to the Ramey Home in Catlettsburg in spring, 1944.

Over the next several months, Boyd County Health Director Dr. Price Sewell organized three house-to-house walk throughs. Kimbler was charged for maintaining houses 'unfit for human occupancy.' But, families with small children did occupy each of his windowless shacks for which Kimbler collected $5 or $10 a month for rent.

Dr. Sewell filed charges against George Kimbler, reported in the Ashland Daily Independent on August 3, 1945:

Catlettsburg- Charged in seventeen

county warrants obtained by the Health Director, Dr. Price Sewell, from Judge E.

K. Rose, seventeen separate County warrants charged: George Kimbler, the owner

of numerous small houses located in the Avondale section of Ashland, with

maintaining a common nuisance. After an inspection of seventeen separate houses

in the Avondale, section which were described as "unfit for human

occupancy." Each instance was made

the basis for a separate charge.

At his trial, George S. Kimbler boasted he owned seventy-five houses and properties in Avondale and around Ashland. This was true. Mr. Kimbler's holdings are documented on five pages in the logbook at the Clerk's office at Catlettsburg.

"There was always a fight or a disagreement somewhere in Avondale. One time I saw men throwing bricks at each other. Can you imagine heaving bricks? After the City built the bridge over Long Run Branch, men gathered there to play dice on the wood planks. There were two killings that I remember: Dooby Sparks shot Fred Fitch, and went to prison over it, but not for long. They were both drunk. I also remember a murder-suicide when a man shot his girlfriend, and shot himself. I was about fourteen. But, I can't recall their names; I grew up in Avondale," stated Annabelle Everett.

"A few homes used hand dug wells and nearly all had out-houses. Most people dipped laundry wash water from Long Run Branch. My grandparents were Julia and Green McMillan. We lived near the Johnson family, and all over Avondale. We lived the longest in a two-story house with a full bathroom. Most of the houses in Avondale had outhouses though. We used gas heaters for cooking and to heat the house.

"Grandpa McMillan had worked in the coalmines, and he was a veteran. So, his little government check kept us going. My mother, Mattie Belle, had a rough time. We came to live with our Grandpa McMillan in Avondale. Mother married twice and offered for us to go with her, but we were settled in Avondale.

Grandpa McMillan kept us close; we didn't often venture down Branch Street. I got to see the start of several fights, and then he'd make me come in the house. We lived next to John Spence and his family at 1404 Branch Street. We attended the Holiness church, where Pastor Kimbler preached, and the Baptist Chapel on Branch Street. I saw the Fannin children sometimes. After George Kimbler died, John Fields lived in Avondale and worked on the old houses for Mrs. Kimbler.

They said the Kimblers made the City build that bridge. But it wasn't built just right and Branch Creek went right on flooding Avondale. Our house on Spence Street was on higher ground."

"Avondale was a pretty place at first, I remember it, but it became a transient white family slum. I remember Mrs. Sullivan. She stayed with different men. She had babies and didn't want to take care of them, so she took them to Gertrude Ramey as they were born. There may have been more, but I remember John Sullivan, and Melvin Terry and at last she took up with a Mr. Elswick."

Jerry Johnson said, "That bridge was more than a walkway to the other side of Long Run Branch. It was the center of all activity in Avondale. The planks served for rolling dice or playing cards, or the men took to the bushes to keep out of sight behind the church. At night, they built little fires. We played ball behind the church, too. Before the bridge was built, and even after it was built, run-off water boiled down Branch Street. People had a terrible time. It flooded up to our alley, but it never came in our house."

The Grand Jury indicted George

Kimbler on January 8, 1945: for greatly endangering the health and safety

of all citizens of the Commonwealth residing in the neighborhood, of Avondale

District and contrary to the form of the statues in such cases.

Signed: Thomas Burchett, Commonwealth's Attorney 32nd Judicial District.

Trial date was set for April 9, 1945 before Hon. Watt M. Prichard at Catlettsburg. Thomas Burchett, Commonwealth Attorney, assisted by A. W. Mann, prosecuted the charges against Kimbler. E. W. Fannin was counsel of record for the defendant, George S. Kimbler.

During questioning at Kimbler's trial, Attorney E. W. Fannin led J. T. Blevins through his testimony in what he hoped was in favor of Kimbler's position:

Fannin: Where is your store?

Blevins: 1238 13th Street. (#1238 is the storefront where the Waugh children were rescued)

Fannin: Who lived there before you?

Blevins: I think

it was Albert Waugh.

Fannin: Tell the jury whether or not you have hot and cold water in the store and a flush toilet?

Blevins: Yes, sir. I have a china toilet, flush commode.

Fannin: You told the Jury you moved into your storefront on December 1, 1944; before you moved in, did you hear tell of a baby lying on the bed there covered with black flies so much that he looked like a nigger?

Blevins: No sir, my youngest child is thirteen years old.

Fannin: You've got a nice clean little store there haven't you? Who paid to have it fixed up for you?

Blevins: George Kimbler paid for it.

Mr. Kimbler was a master. Faced with weak questioning from the Prosecutor, either by luck or design, Kimbler turned the Court's inquiry into technical operation discourses on the merits of outside frost-free toilets and how to turn on the water for each house. He described in detail, a cut off valve for residents to use, as they needed. But residents testified they were unaware of such a gadget, and that often they had no water. Only one witness for Mr. Kimbler spoke to the issue of waste disposal, but assured the Court it was repaired promptly. He described the close proximity of houses along Branch Street as: "I can stand in my door and talk to him in his door."

Like her neighbors, Lou Emma Jacobs, 1233 Spence Street, did her best to bolster her living conditions with a little extra work, but she was trapped in cross-examination by the all knowing and, in her case, all telling cross-examination:

Mr. Mann: Do you know of any people in that immediate neighborhood there with such as syphilis and gonorrhea or other venereal diseases?

Miss Jacobs: Well, I don't know. I don't examine people like that.

Mr. Mann: Did the

doctor examine you?

Miss Jacobs: Yes, sir.

Mr. Mann: You are a syphilitic patient of Dr. Sewell now?

Miss Jacobs: Yes, sir.

Among Kimbler's witnesses was Virgil Spradlin, who claimed he moved to Avondale a year earlier. Frank Starcher also said he had lived in Avondale for four months. Lon Howard, a new Avondale resident, also testified, like Spradlin and Starcher that he had not noticed an odor or sewage waste on the ground. Under cross-examination, Spradlin, Starcher and Howard also admitted to being convicted felons for the crimes of Grand Larceny.

William Casady, another witness for Kimbler, told he lived in four different houses in Avondale, moving each time to a better house and to Spence Street near Mr. Kimbler prior to the Trial. Other Kimbler witnesses had 'just moved in' since the seventeen warrants were issued.

Was this a case of musical witnesses for George Kimbler? What happened to the former residents, who had actually complained? It was a mystery for the Commonwealth's Attorney. The Jury was not put off

We the Jury agree and

find the defendant guilty and fix his punishment at a fine of Two Hundred

Dollars ($200) and Twenty Days in Jail.

Catherine DeHart, one

of the Jury.

The fees for the action amounted to $323.39 for George S. Kimbler

On April 10, 1945, Kimbler filed for a new trial citing prejudice on the part of Fire Chief Burris Hensley, for taking one of the jurors for a ride to view Avondale.

On June 9, 1945, Kimbler filed his Bill of exceptions to the Trial. The Appeals Court denied his claims. George S. Kimbler put up a good fight. He paid his fines and used his influence because he never served time in Jail. And he did not clean up Avondale.

On December 5, 1946, this letter was sent to:

John T. Diederich

Attorney at Law

Professional Arts Building

Ashland, Kentucky Re: Commonwealth vs. George Kimbler

Dear Mr. Diedrich:

About a year ago the Court of Appeals confirmed the conviction of Mr. Kimbler and the court, upon agreement of myself and Mr. A W Mann, permitted a stay of execution of Mr. Kimble's prison sentence for the reason that he had agreed to correct the conditions in his Avondale properties. On November 15, 1945, I received a letter from Governor Simone S. Willis, which was addressed to you and to me, stating, in effect, that he would grant executive clemency, provided Mr. Kimbler corrected the conditions.

Since that time I have had numerous complaints from the Health Department and on a particularly long report, dated February 11, 1946, in which numerous properties were listed as being in a most unsanitary and unhealthful condition.

The Inspector for the Health Department has been complaining to me recently. Not only that but different members of the Board of Health have also made complaints. I have also had many complaints from citizens, wanting to know why something had not been done with that matter.

It has become a very embarrassing thing to me as I know no logical reason I can give at this time why he has not corrected conditions in his Avondale properties. I do not want to take any action on this smatter until you have given a complete change to see the court in regard to same: therefore, I wish you would look into this matter at your earliest convenience. Thanking you for your cooperation, I am

Yours very truly,

Thomas Burchett

Commonwealth's Attorney

Commonwealth Governor Simeon S. Willis was no stranger to Avondale District. He had practiced law in Ashland until 1943, less than one year earlier; he was elected Governor, the first Republican in forty years. He served the Commonwealth from 1943-1947.

Three years later, Mr. Kimbler died leaving Avondale unchanged; at least unchanged from being a slum. It was the same unkempt district as it was when the six abandoned Waugh children were rescued in April 1944, or when Andrew Fannin was born in the shack at 1414 Branch Street in 1962; and it remained so until it was razed and burned in 1965.

George S. Kimbler died at seventy-three on May 13, 1949. For seventeen years, until Urban Renewal made its offer, his widow maintained her husband's policy, to rent out the windowless shacks in Avondale along Long Run Branch, to poor people.

Transformation did not come easy to Avondale, but at last, it came. It came, not through development as engineers proposed, but through restoration. The final curtain was pulled across the 1200 block of 13th Street in 1966; there was no response from anyone to the City Directory. When the dust and smoke cleared, new trees and grass grew along Long Run Branch in 1974, Avondale was transformed. But, what of Christina Weidenheller's legacy of love? What of her generosity for the children of Avondale? What of the Tabet sisters, and Gertrude Ramey?

Eleanor Johnson remembers, "Ms. Weidenheller had so much love she hugged us all the time and called us by our own names. She made no difference in black children. She told us we were pretty; how special we were. "God loves you," she called to us. Years later when I worked at Kings Daughters, she saw me from far off. She called to me with her sweet voice and came to hug me. We can run on love like hers for years, and we have. Love like hers lives on in my heart; it keeps Avondale alive."

After a long search, Beryle Williams widow of Pollard Baptist Church Superintendent Poe Jeffrey Williams, held up the precious photos of the Avondale Baptist Mission and the children,

"You never know when you've touched a life."

-The End-

Special help came from:

Bob Bickers, Publisher HGA newsletter

Marilyn Amsbaugh, Granddaughter to George S. Kimbler

Ester Kimbler Justice Burroughs, daughter

Annabelle Everett & Nada Tabet

Boise City Engineers

Cathy Fisher, Boyd County Clerk's office

Judy Fleming, Jim Kettel & James Powers Genealogy Library

Tracey Kelly, Circuit Court

Klaiber & Wolfford

Jerry, Eleanor & Frances Johnson

Walter S. Johnson, Sr. for writing a detailed history for his Johnson, France and Cosby Family.

Beryle Williams donated original photos and documents to the archives

Nora Christina Hatcher-Weidenheller 91, died in 2000.

A partial list of black families in Avondale:

Eddie Collins and Aunt Libby Collins

Ada Cosby

Vivian Evans Homer B. Evans

Marjorie and Luther Ealey

Willard Eulen and Miss Eulen

Louise Farrow and Hope Farrow

Snoopie Hamilton

Hobby Jacobs

Wm. and Verna Kelsor

Addie May

Opal Phelps and 'Mr. Red' Eular Phelps

Miss Pinkey.

Opal and Dallas W. Thomas

Lydia Justice-Edwards

justiceedwards@qx.net

For other RameyHomeWaughChildren interviews:

RootswebFreepages.

Background material for this article is archived at the Boyd County Public Library Genealogy Department.